Yiquan (Mind Intent Boxing) has always been an integral part of both external and internal Kung Fu, and it was once the name of Xing Yi Quan (Form and Will Boxing). Over the years, Yi Quan has often been left out of the equation not only in Xing Yi Quan but in a host of martial arts. Noted internal kung fu stylist, Wang Xiangzhai (a student of Xingyi teacher Guo Yun Shen) placed Yi Quan at the core of the internal martial arts system he created known as, "Dacheng Kung Fu:" a system based on the core principles (and less on the forms) of the internal martial arts of Xingyiquan, Baguazhang, and Taijiquan.

Yi Quan (I Chuan)

by Gerald A. Sharp

Animation: Embrace the Tree from Yi Quan applied to Push Hands (Tui Shou) application.

During the Ming and Qing dynasties (1368-1911 A.D.), the concept of Yi

Quan training had already become integrated into many types of traditional

Chinese Kung Fu. It may have been best known as a core practice of many

types of Nei Jia (or, internal shape) Kung Fu. While the term Yi Quan has

been applied most often to internal martial styles, it has also been a part of the

internal practice that was an element of both Northern and Southern

external Kung Fu systems. The idea that Yi Quan was only a part of

internal martial styles or that it was developed later in the

1950’s or 1960’s in the last century ignores the

internal, meditative, practice of many styles of traditional

Kung Fu. This practice has been a part of both Northern and Southern styles and the practice spans both external and internal styles of kung fu.

During the Ming and Qing dynasties (1368-1911 A.D.), the concept of Yi

Quan training had already become integrated into many types of traditional

Chinese Kung Fu. It may have been best known as a core practice of many

types of Nei Jia (or, internal shape) Kung Fu. While the term Yi Quan has

been applied most often to internal martial styles, it has also been a part of the

internal practice that was an element of both Northern and Southern

external Kung Fu systems. The idea that Yi Quan was only a part of

internal martial styles or that it was developed later in the

1950’s or 1960’s in the last century ignores the

internal, meditative, practice of many styles of traditional

Kung Fu. This practice has been a part of both Northern and Southern styles and the practice spans both external and internal styles of kung fu.

If one has to point to a single major kung fu style where the traditions of Yi Quan practice reside most nearly at the heart of the system, it is Xingyiquan (Form and Will Boxing). In fact, an early name for Xingyiquan was Yi Quan. If there is now a distinct practice of Yi Quan that is completely separate from Xingyiquan, it is an indication that traditional Xingyiquan is being lost and what is now being taught as Xingyiquan is separated from the roots of the system. What we see more and more today in both arts is a further separation from the roots: the intent of the originators can no longer be recognized. To the extent that standing meditation is a practice that spans many traditional kung fu styles, removing Yiquan practice indicates a failure to pass on these styles: this is particularly true of internal or Nei Jia styles of kung fu.

|

1. The Practice

Yi Quan, as well as Xingyiquan, has seven stages of practice as follows:

Notice that the idea of "empty force" is not anywhere on the list of the seven stages of Yi Quan practice. Some practitioners possess a lightness or deftness of touch; these practitioners use much less force in all phases of the martial interactions from push hands to fighting. Both inside and outside of China, the term "empty force" is only loosely defined, and it has been used to describe everything from those who are light and undetectable to those who wave their hands and seduce the gullible. What is well defined in Yi Quan is the concept of Wuji, which is manifested in both seeking equality of the visceral components and Taiji, or harmonizing opposites.

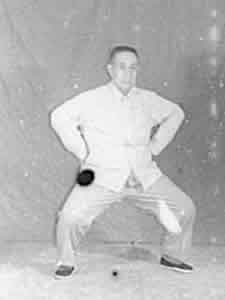

Ma Yueh Liang practicing Zhanzhuang. |

2. Development / History

Yi Quan practice has a long history in many types of Chinese Martial Arts, both internal and external. Yi Quan has been a core practice in a number of styles. The Chinese internal martial arts are also known as Nei Jia (or, internal shape) Kung Fu. The external martial arts are also known as Wai Jia (or, external shape) Kung Fu. Yi Quan was originally developed from the San Cai Shi (or, San Ti Shi) as a standing pole posture that students stand in between practicing Xingyi's various sets. However, even this practice seems to have been left out of Xingyiquan systems that have focused on more external boxing practices. Even the practice forms can be done in such a way that the internal aspects of the art are devalued or even left out completely as well. These internal aspects do not only involve the meditative aspects of the art but also the sensitivity training methods such as push hands practice, which is the foundation for the sophisticated development of grappling and related skills (that are sometimes devalued in external striking methods). |

|

3. Wuji

To attain the Wuji, or Void, the idea of completely emptying is nonsense. While you can slow your pulse from pounding, you can’t stop it completely. While you can calm your breath from being heavy and achieve breath that is light and even, you can’t stop breathing completely. What I have learned, is that Wuji is an undifferentiated state: there is no preference between left and right, top and bottom, front and back, and inside and outside. Most importantly, Wuji is a state of undifferentiated balance that is achieved through non-action -- or the least amount of effort. This is distinct from the differentiated balance of Yin and Yang, (although it is easier to find the balance between Yin and Yang in your practice after you have found Wuji).

|

4. Explosive Force and Application

There are many examples of the application of “fajing” or explosive force. The most familiar examples might be found in the Japanese practice of Kendo. The picture of someone wearing protective gear and standing still with a wooden practice sword in an overhead posture waiting for precisely the right moment to strike explosively is apt. Explosive force or "fajing" can also be found in Chinese internal martial arts, -- and while it contains a component of surprise -- it is also emphasizes a high level of subtlety. This is such a key point that striking is usually not taught until aspects of these subtleties are comprehensively mastered. The reason for this approach can be found in watching practitioners who can issue fajing ("explosive force") without overt preparation from any posture and within the context of any situation. Skilled practitioners often vary greatly in how they issue fajing each time they practice forms or joint hands practice. |

|

5. Wang Xiangzhai and Other Modern Day Practitioners of Yiquan

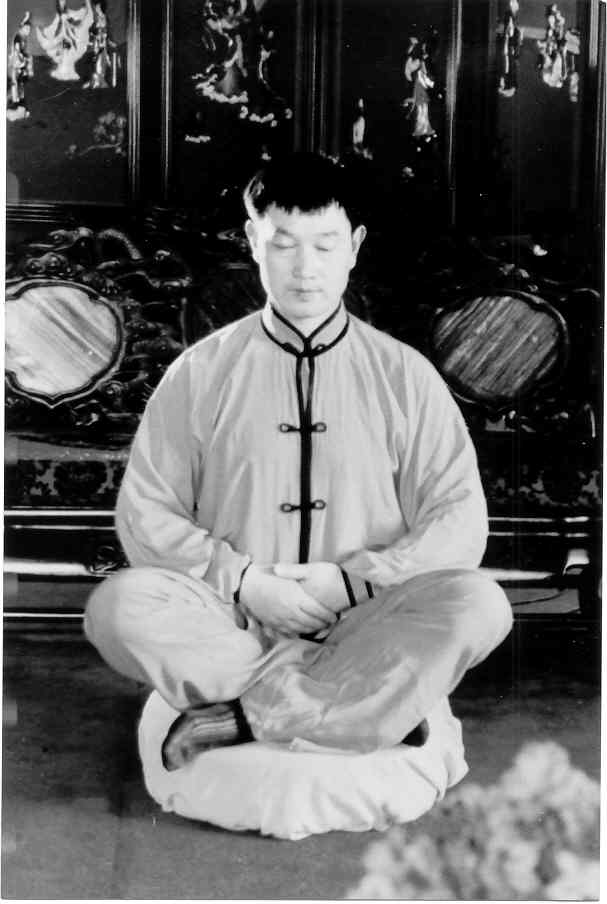

Wang Xiangzhai is often mistakenly credited with fathering Yi Quan. While he undeniably was a major exponent, Wang Xiangzhai did not father the practice of Yi Quan. He did father a no-nonsense approach to internal martial arts called, “Dachengquan” which is a complete Nei Jia Kung Fu system that combines aspects of Taiji, Xingyi, Bagua and includes Yi Quan practice. This art has sometimes also been called “Yi Quan,” but that is already the name of an older underlying practice method that runs through most of Chinese Internal kung fu. Yi Quan is also known as Standing Pile Stance Kung. Chen Jie Feng in seated meditation. |

6. Yi Quan’s Future

It is interesting that from the time Wang Xiangzhai left Shanghai until he settled in Beijing, Wang de-emphasized more formal Xingyiquan practice and developed his Dachengquan with an emphasis on Yi Quan, two person practice, and free sparring. Some of Wang Xiangzhai’s students and grand-students that remained in Shanghai still practice Xingyiquan to this day as well as Wang Xiangzhai's “Yi Quan:” They maintain that the art they were taught has the integrity of the original practice. Why did Wang Xiangzhai make the change? Perhaps Wang became fed up with what he saw as the disintegration of the true internal practice. Examples of this disintegration include the introduction of the Simplified 24 form Taijiquan; the over-reliance on forms and scripted joint-hand methods; demonstrable loss of skill in applications; and failure to achieve spontaneity. In each generation of students, fewer people are able to reach a high level of practice. |

|

7. Recovering the Yi

Throughout the 20th century, this same process of watering down of the internal martial arts has continued in order to make them more commercial and – supposedly – more "accessible” for the general public. Despite the efforts of Wang and others who sought to “raise the bar” against this development, the flood tide of mediocrity seems to still be rising. Perversely, we now have an attempt to make Yi Quan itself more accessible to the public. A mystic “New Age” approach has emerged with the emphasis on a few of the standing postures only. These versions of Yi Quan are simply the “Yi” without the “Quan.” This separation of “Yi” from Yi Quan is like Yi Quan’s amputation from the Xingyiquan, Dachengquan, or other comprehensive martial arts systems. |

8. Finding Stillness

That’s the fundamental key to Yi Quan’s practice: stillness is selected over any external movement. When properly practiced, this approach helps guide one to find motion in stillness and stillness in motion: this is a foundational concept of Chinese Internal martial arts: yang within yin and yin within yang. Any movement other than relaxing is perceived as an external force that can potentially be exploited by an opponent. This is why Guo Yunshen – Wang Xiangzhai’s teacher – and other Xingyiquan practitioners of Guo’s generation such as Liu Qi Lan practiced Xingyi in a slow, deliberate manner, stood in the San Cai (San Ti) posture, and practiced the traditional standing postures that have become known as Yi Quan at the core of their Xingyi practice.

Group Practice, Long Hua Temple Park, Shanghai, China |