by Gerald A. SharpWu Style Tai Chi

Animated Image: A martial application of Wu style Taijiquan (Wu Chian Ch'uan style T'ai Chi Ch'uan). This is a variation of the transition to Single Whip associated with the Fast Set. Other martial applications can be found as links on the Applications page on this web site.

Wu style Taijiquan was created by Wu Jian Quan. He was the son of Quan You who was one of the best students of Yang Luchuan (creator of Yang style). Yang Luchuan was one of the most renown martial artists in China at a time of upheaval. He fought many challenge matches with adept martial artists in several regions of China to begin his reputation. In Beijing, Yang Luchuan trained the Imperial guard, private troops, and even the Emperor's family. Taijiquan has a Yoga-like character that has given the practice a reputation as a very useful stress relief and health exercise. It has been suggested that Yang Luchuan could have succeeded in training adept professional solders in a time of conflict by teaching a watered down martial art: this could not have been true. Quan You was certainly adept as a martial artist or he would never have attained the position he held in the Royal Army, since he was not from a family of rank. Wu Jianquan also had a reputation as a great martial artist - as did Ma Yueh Liang. The Yoga-like aspects of Taijiquan make it difficult and time-consuming to learn. This is true of all styles of Taijiquan. Wu style has an extremely minimalist approach to movement, but it is still an effective martial art. Wu style Taijiquan was created in the Twentieth Century by Wu Jianquan. Because Wu Jianquan lived until the middle of the Twentieth Century, and his daughter Wu Ying Hua and son-in-law Ma Yueh Liang both lived until the end of the Twentieth Century, the branch of Wu style centered in Shanghai has had little opportunity to suffer transmission loss over several generations of instruction.

When Yang Luchan, creator of Yang Style Taijiquan, was teaching internal martial arts to soldiers of the Royal Army during the Qing Dynasty, three students excelled and attained the essence of his skill: Wan Chun, Lin San, and Quan You (1832-1902). As legend has it, Wan Chun acquired heightened energy and essence abilities, Lin San inherited strategic and tactical skills, while Quan You, a Manchurian, secured the talent of neutralizing an opponent's force.

As Yang Luchan got on in years, he recommended Quan You to study with his son, Yang Banhou. Yang Banhou kept few students, and was fascinated with the small frame of Yang Style Taijiquan, which focused primarily on penetrating the opponent's center of gravity (as well as neutralizing an opponent's aggression) with smaller, more intricate movements.

Building on the ideas of efficiency and simplicity, Quan You developed his own combative Taijiquan form that came to be known as the "Fast Set." This form was not solely based on his studies with Yang Banhou, but was a synthesis of all his studies with both Yang Style's creator, Yang Luchan, as well as Banhou. This combative form would be passed onto his son, Jianquan who took the Chinese surname of Wu. Wu Jianquan would carry on his father's legacy by developing a "Slow Set" from the "Fast Set," which he unveiled publicly from 1911-1919 in Beijing when he was invited to teach at the Physical Culture Association by Xi Yuiseng (1879)-1945) along side Yang Shouhou (1862-1930) and Yang Chengfu (1883-1936), both legendary practitioners and descendents of the Yang family.

|

1. The Original Fast Set

The Wu Style developed from both Yang's Big and Small frames. Quan You harnessed the great power and dynamics from Yang's original large frame, and absorbed the practicality and efficiency of Yang's small frame. The original Wu form Quan You developed came to be known as the Wu Taijiquan Fast Set, or "Wu Taijiquan Kuai Quan." In the process of his investigations and development of the "Fast Set," Quan You discovered power that pushes, pulls, and twists from the center of symmetrical structures, and combined with centrifugal force created movements that progressively spin forth from tapered geometric shapes. The centrifuge dynamics, inherent in the form's practice, perpetuates a momentum that appears to be both endless and seamless before it is brought to rest and is still.

When the form's concepts are introduced in joint hands operations, the momentum is derived from any opposing force, and is aimed at neutralizing and opposition. Different than the "Slow Set," or long form of Wu Style Taijiquan where stillness is such an integral part of the neutralization process, the "Fast Set" utilizes the concept of the practitioner themself as a centrifuge, and focuses more on guiding the opponent's force in a spiraling manner. Furthermore, leading the opponent's force into a dead spot where there can be no escape, especially if the aggressor is committed to "hanging on" to their forceful intentions. From the onset, the Fast Set may be perceived to be Taijiquan combined with some semblance of Xingyiquan and Baguazhang. However, the Fast Set has a unique character and flavor all its own. As previously stated, it is a very different set than the Wu Slow Set developed by Quan You's son, Wu Jianquan. To say the Fast Set is the Slow Set speeded up with fast movements, (regardless of how soft the movements may be) is a gross error. Despite the fact, that some seemingly legitimate practitioners may practice the set this way and call it the Fast Set does not mean it is the authentic Fast Set that was developed by Quan You and demonstrated publicly by Ma Yueh Liang in Hong Kong and Germany, as well as in China in the late eighties. Concerning the slow set's lineage, there are practitioners who claim a slow set lineage to Quan You, and it is highly possible both father and son had a hand in the slow set's development. However, Wu Jianquan's contribution and development of the form cannot be dismissed. According to documents kept by the Chian Chuan Taichichuan Association of Shanghai, until Wu Jianquan unveiled the Wu Slow Set in 1911 in Beijing there was no Wu Slow Set. Instead, there are records both inside and outside the Association that indicate that Wu Jianquan taught a slow, small frame set in Beijing in 1911-1919. There are no records that Quan You taught publicly in a similar vein. If anything, there are indications that Quan You's Slow Set, or Man Quan, practice was the Yang Style Small Frame. |

2. The Development of Wu's Tai Chi

Ma Yueh Liang, Wu Jianquan's son-in-law, often commented on the similarities between Yang's Fast Form and Wu's when he saw Yang Shouhou perform the form. According to Ma, the real development of Wu Style took place when Wu Jianquan with his father began experimenting on reinventing the small frame with what Quan You saw as the essential, simplistic movements that carried forth the maximum of the dynamics from the fast set. In other words, the fast combative form Quan You created was taken and put to the test as to what was essential and useful. From this series of "experiments" the Wu Style was born. When it premiered in Beijing in 1911 it was wondrously received. While the Yang Style was perceived as a huge development towards the internal from the Chen Style, the Wu Style with its small frame was perceived by some as an even larger step towards combining both form with formlessness and motion with stillness. After nearly 20 years of teaching in Beijing, Wu Jianquan moved to Shanghai in 1928 and in 1935 founded the Chian Chuan Tai Chichuan Association aimed at teaching Taijiquan publicly and improving people's health. In Wu Jianquan's absence from Beijing, there were teachers who wanted to get on the "Nei Jia Kung Fu" bandwagon and have their own lineage. That's when some began touting a lineage with the, then, late Quan You. What was actually being practiced and taught was likely either an offshoot version of Wu Jianquan's Slow Set or a variation of Yang Style. This is evidenced in the stances that can be observed, namely, in which, the bow stance has the back foot turned out 45 to 90 degrees. One of Wu Style's chief developments in the Slow Set practice was to keep the feet parallel, or nearly so, in order that the practitioner's entire energy was focused forward on the opponent as much as possible. This is not a criticism of Yang Style when I say this, but rather proof of Wu Style's emphasis on parallel feet, both Ma Yueh Liang and Wu Ying Hua would demonstrate many times how a practitioner with their back foot turned out could be easily pulled, pushed, or twisted off balance.

|

|

3. Natural Order

The order one learns Wu Style Taijiquan is usually as follows. This varies both student to student, class to class, and teacher to teacher:

However, for practitioners who become preoccupied with learning the weapons, inner door forms, or push hands for that matter, and they haven't learned how to practice the Slow Set or, Man Quan correctly, they could very well be wasting their time. This is not an elitist statement, but a practical one. For even the most advanced practitioner, regardless of style, the Slow Set is not only the beginning point of the style, it is the end as well.

Like all styles of Taijiquan, or any internal martial arts for that matter, the movements need to be "natural." The word natural can be extremely misinterpreted or given a general or even vague explanation. However, while nature may be on the surface less orderly than the seemingly organized lives of human beings in modern civilization, it does have a highly sophisticated order not normally seen with the naked eye. |

4. The minimalist approach of Wu style

One useful concept to apply in your practice is that energy often moves in waves and operates at a particular frequency. These waves of energy contain a crest, body, and trough. Like natural waves of energy, the body can be trained through correct Taijiquan practice to move with a crest, body, and trough, and does so by moving hand, body, and foot in a close-knit sequence. The classics often describe how the movements in Taijiquan ought to be like a "string of pearls." That when one part moves, all others follow in succession. It is unfortunate to see Taiji players often hooked on the slow, smooth feeling of the movements and ignoring the reality of the natural order of the movements. For example, when you reach for something arbitrarily in life, your hand will move first, then your body will follow, and finally you will adjust your feet, before you return the energy back out to your hand to create a more secure grip on the object. If one ignores natural movement in Taijiquan, they will most certainly lead them self into a false sense of reality. All the while believing that they have discovered chi or even Nirvana. However, if Taijiquan is ever tested in joint hands or push hands practice, this false sense of reality is often exposed. For example, some practitioners focus on creating all movements from the waist. This statement is - in fact - correct, but this approach is often implemented incorrectly. If the waist "leads" all movements or is the first part of the body moved, then in actuality what the practitioner is doing is exposing their central equilibrium. They are "putting the cart before the horse" in their practice. Therefore, it is wise to keep the waist at the center of all movements, and maintain the arms and legs as if spokes on a wheel. This is the genius of Wu Style Taijiquan, which seems almost void of outer waist movements and minimizes the externalization of any outer physical movements. If Wu Style is practiced correctly, it can be difficult to see any such wave or frequency. Moreover, the advanced practitioner easily conceals movements, which is a hallmark of Taijiquan; that is, that "Steel is wrapped in cotton." |

| 5. Precision as a key element of practice When first learning Taijiquan, the practitioner usually focuses on precision of the outer movements. They also are likely carrying stiffness somewhere, and this can take years to undo; especially if one ignores natural movement as previously discussed. As time goes on, those who persist in natural movements begin to focus more on how slowness leads to stillness and vice-a-versa, and begin to passionately pursue Yin and Yang in practice. That is, they weight the right and empty the left, push the front and pull the back, lift the crown yet drop the sacrum, sink the roots and lighten the shoulders. Over and over they train every aspect of their mental, physical, and spiritual being. Finally, as they persevere in their practice, they discover that there is no end to both differentiating and merging the endless landscape of Yin and Yang, and begin to discover Yin within Yang and vice-a-versa. In this light, Taijiquan takes its place as one of the supreme ultimate disciplines and is a credit to the ingenuity of human beings. |

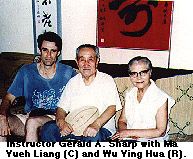

6. Ma Yueh Liang and Wu Ying Hua

Ma Yueh Liang's Wu style Tai Chi Chuan. This link takes you to a page that is an appreciation of Ma Yueh Liang and Wu Ying Hua, the son-in-law and daughter of Wu Jianquan.

|

7. Push Hands Wu style pages on chiflow.com include material on Push Hands (Tui Shou):

|

8. Chi Kung

Chi Kung (Qigung) pages

Also see the other Tai Chi Chuan pages on the chiflow site.

Go on to Wu style page 2. |

(Left: Wave Hands Like Clouds application as a demonstration of the Wu style centrifuge concept.)

(Left: Wave Hands Like Clouds application as a demonstration of the Wu style centrifuge concept.)