Origins of Taijiquan (Tai Chi Chuan)

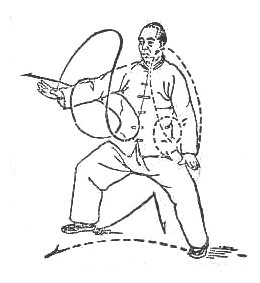

LEFT: Application of Wu style Taichichuan Wave Hands Like Clouds against a standing arm bar.

Tai Ji Quan (T'ai Chi Ch'uan) is a branch of the traditional internal martial arts (or Nei Jia Kung Fu) that spread in China over 300 years ago at the beginning of the Qing Dynasty. T'ai Chi Ch'uan became even more popular around 1911, when it was first taught publicly in Beijing by Yang Shou Hao, Yang Cheng Fu (Zhenpu), and Wu Chian Chuan (Jianquan). Stories abound about Taijiquan's origins, and there is growing evidence that it may have first surfaced around the eighth century during the Tang Dynasty. T'ai Chi Ch'uan may be a modern version of something much older. In general, Taijiquan and more generally internal Chinese martial arts are associated with Taoist practices and the Wudang mountain. The five major modern styles of Tai Chi Chuan are generally viewed as being Chen style; Wu (Hao) style; Yang style; Wu (Jian Chuan) style; and Sun style.

by Gerald A. Sharp

Fist of Legend

While it has become fashionable in some circles to view T'ai Chi Ch'uan as only a health exercise, this is not the traditional way to view the art. Even the T'ai Chi styles that have many followers exclusively interested in health benefits were created to be martial arts. Each style of Tai Chi Chuan has traditionally included weapons training. The general approach used in Taijiquan is sometimes subtle and may be at odds with the preconceptions of casual observers. The specific approach can have a somewhat different flavor for each style of T'ai Chi Ch'uan.

Application - Wu style knife ("Dao" or Single edged Broadsword) against a sword ("jian") .

Many practitioners both inside and outside of China recognize Zhang Shanfeng as the founding father of the art.  Legend has it that Zhang was a wandering Taoist priest from Wudang Mountain who, during the Yuan Dynasty (15th Century), supposedly developed a gentle, sophisticated meditation for longevity, while watching hard style monks practicing their more "external" martial arts and chi kung on Wudang mountain. Another account claims there was an alchemist (also from Wudang mountain) named Zhang Shanfeng who developed Taijiquan during the Song Dynasty (12th Century). Xu Xuanping, a wizard during the Tang Dynasty (8th Century) is also recognized in some circles as a forebearer of the art in other related stories. Often these Taijiquan origin tales involve Zhang Shanfeng, and yet another obscure tale depicts him receiving inspiration from watching a bird unsuccessfully trying to carry off a snake with brute force, while yet another bird stole the prey by using more sophisticated, softer dynamics. Although, more often than not, these stories do not help very much in determining the historical origins of Taijiquan.

Legend has it that Zhang was a wandering Taoist priest from Wudang Mountain who, during the Yuan Dynasty (15th Century), supposedly developed a gentle, sophisticated meditation for longevity, while watching hard style monks practicing their more "external" martial arts and chi kung on Wudang mountain. Another account claims there was an alchemist (also from Wudang mountain) named Zhang Shanfeng who developed Taijiquan during the Song Dynasty (12th Century). Xu Xuanping, a wizard during the Tang Dynasty (8th Century) is also recognized in some circles as a forebearer of the art in other related stories. Often these Taijiquan origin tales involve Zhang Shanfeng, and yet another obscure tale depicts him receiving inspiration from watching a bird unsuccessfully trying to carry off a snake with brute force, while yet another bird stole the prey by using more sophisticated, softer dynamics. Although, more often than not, these stories do not help very much in determining the historical origins of Taijiquan.

On the one hand, there is good reason to be dubious of many of the tales that surround the origin and early development of Taijiquan. Even today there are people that learn a little Taijiquan, hang up a credential from Mountain so-and-so and claim that they are a lineage holder of an obscure style of Taijiquan that is somehow linked to the mysterious ancient history of Taijiquan. This sort of thing happens all over the world, both inside and outside of China. Nor is it only confined to the internal style martial arts (such as Taiji, Xingyi, or Bagua) but it happens in all martial arts.

On the other hand, there are some overarching themes that seem to have some element of truth. Many of the postures of Taijiquan have much in common with pictures of postures that are quite old. Most accounts give credit to the Taoist sojourner, Zhang Shanfeng, as the father of Taijiquan. While these tales seem to be shrouded in legend, there is almost always a link to either Taoist teachers or Taoism. Most specifically, stories often link to the Taoists of Wudang mountain. There is also enough ambiguity in what we do know about the development of Taijiquan that some of the claims of "obscure" styles must be considered very seriously. An example of this sort of claim is that of the Zao Bao style of Taijiquan. Thought at one time to be only a branch of Chen Style Taijiquan, there's evidence that suggests that it may be not only the original style of Chen Style but of all styles. Both Wudang Mountain style and Zao Bao style Taijiquan are legitimate styles with credible claims in both camps as having a role in Taiji's origins, and they are not the only ones. There's evidence that may point in yet another direction.

Left: Chen stylist Gui Liu Xin

Left: Chen stylist Gui Liu Xin

|

1. Chen Wangting Research by the martial arts master, Tang Hao (1897-1959), during the 1930's and historical records from Wen and Anping Counties both indicate that the first known practitioner of Taijiquan was Chen Wangting. These references were documented by Gu Liu Xing, a noted practitioner, historian, and writer of Taijiquan practice. In the 1660's Chen Wangting led troops to beat back assaulting bandits about twenty years after the overthrow of the Ming Dynasty. The historical records include accounts of his martial arts and military skill. It is said, after order was restored, Chen Wangting retreated from the world , and became a recluse of sorts. Chen was influenced by Taoist philosophy and began to explore the essence of energy and strength. The story is repeated that before he died Chen Wangting said that personally to avoid depression he practiced internal boxing, involved himself in field work in the appropriate season, and spent his leisure time teaching disciples and his descendants so that they could be contributing members of society. Additionally, a viewpoint that has surfaced, in recent years, is that Chen Style Taijiquan was developed from Shaolin Temple Martial Arts. This could have some credibility since Shaolin Temple and Chen Village are both located in Henan province and they are not far from each other. However, this could also be a way to promote tourism in the area, since Shaolin temple in recent years has been set up as a tourist attraction for the public with a modern wushu training facility and trinket salesman line the streets outside the temple. |

2. Wudong Mountain Taoist Martial Arts

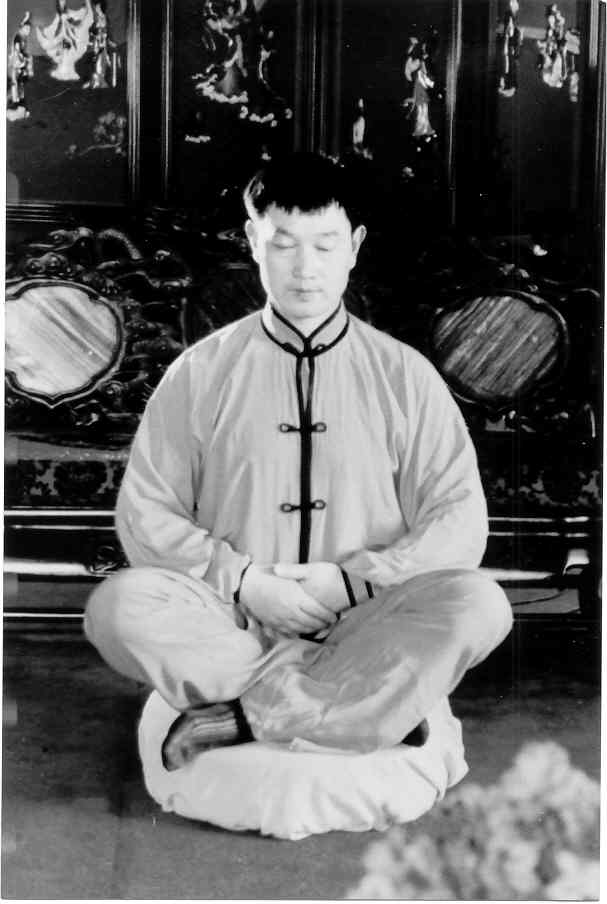

The late Pei Xi Rong, internal arts master and famed author of many books on Wudang styles, Baguazhang, Xingyiquan, etc., was one of five who held a seal for the Jiulong Men (Nine Dragon Gate) Martial Arts from Wudang Mountain. He authored a book featuring the Wudang Mountain sect's entire canon, including both their internal and external practices. This book included a Taiji and Bagua form. The Taiji form looked in many ways like what we see today as a combination of both Traditional Yang and Wu (Jian Quan) styles. If this form has the history that Pei Xi Rong believed it had, it would support the notion that there's some truth to the legend of Yang Luchan having been exposed to Taoist internal arts. Anyway, the Baguazhang presented in the book, and as practiced by Pei, looked very much like Liang Zhen Pu's (Li Zhi Ming) Lao Bazhang, or Old Eight Palms. Because of my exposure to Pei Xi Rong, and other Wudang Masters that I've met, I find their arguments to be credible that their form was the original Taijiquan form. From what I have seen (inside or outside China) of Wudang style kung fu masters (or others with claims to "Old Styles") practicing their arts, as well as the fact that some disciplines have been (and still are) shrouded in secrecy, I cannot dismiss them and say that Chen style Taijiquan was first. |

|

3. Zhaobao Style

Picture: Chen stylist Zhou Yuan Long The Zhaobao style is another group that lays claim to the early origins of Taijiquan. Some of these practitioners don't deny that their style is passed down from Chen Qing Ping, known as the exponent of small frame Chen style. What they do question is the relationship of their style to modern Chen village family style Taijiquan. According to them, the Zao Bao style seems more complete in scope and practice, as compared to other variations of Chen style. It is well known that there were many developments made by fourteenth generation Chen family style teachers which changed Chen style significantly. Therefore, if there is truth to the Zao Bao stylists' claim that their practice originated with Chen Qingping, and that this teaching predated the fourteenth generation Chen family Taijiquan teachers, then the Zao Bao stylists may well be practicing an older version of Taijiquan. That is, what the Zao Bao group was handed down by Chen Qing Ping was in fact the original Chen style Taijiquan. |

4. How could there be just Five Styles when there are so many? Another reason for considering a more thorough evaluation of the styles of Taijiquan is that it might assist us in separating fact from fiction. For instance, I've seen many versions of Wudang Taijiquan. I saw a Taoist Abbot from Wudang Mountain practice the first series of his style in Yongnian once. It was connected, powerful, mixed with external and internal concepts. On the other hand, Pei Xi Rong's practice was slow, and reminiscent of a combination of Yang and Wu (Jianquan) Styles with some, very limited, expressions of fa-jing (explosive force). Because of these differences, there is a real need to identify and categorize not only the differences in the forms, but also the apparent differences of principles that exist between styles. However, any such categorization should be a way to begin to discover and identify missing links. It needs to be an anthropological effort and not a way to create a perpetual establishment that judges every style and variation of the style according to a set of assumed rules. This is exactly what we see happening in both Taijiquan organizations and at tournaments -- especially in America. In China, they have a great way of dealing with - and welcoming - diversity that is only starting to catch hold in the West. Tournaments have an open division (the largest of all divisions) with sub-divisions of both known styles, obscure styles, and virtually unknown styles. When the person does their form or demonstration, they do it in front of a panel of about 20 or so judges who rank the performance and award gold, silver, or bronze medals are awarded. Contestants are judged by a panel of professionals (or would be professionals) who not only have an interest in what they see as quality, but also in finding out more about the practice of Kung Fu outside of their own style. So while China may appear extremely controlling on the surface with the idea of the Five Major Styles, and the organization of "government developed" forms and styles, they certainly are doing a better job than so called "World" organizations of martial arts (again I'm speaking mostly in America) of maintaining an open mind in seeking Taiji's origins.

Taijiquan Push Hands (Tui Shou) |

|

5. Seeing the Value

The trap in this claim of priority (that Chen style is the mother of all the other major styles of Taijiquan) is that this widely accepted viewpoint treats all the other Taijiquan styles as some imperfect refection of Chen style Taijiquan. Instead of a rational evaluation of the choices that one style of Taijiquan makes compared with another, the claim that all the other styles are watered down imitations of modern Chen style is irrational and unsupported by the facts. Modern Chen style is not the art that was practiced at the branch points when Yang style or Wu (Yuxian - Hao) style split off. It is fashionable in some circles to discard all styles, but Chen style as having value only as health exercises. Because the external aspects of modern Chen style make more sense to external style martial artists than the internal practice of the other styles, nothing but the external component of Chen style is viewed as having value as a martial art. This viewpoint dismisses the history, development and uniqueness of Taijiquan - including that of Chen style. If this fixation on an external version of Chen style becomes so pervasive that it leaves no room for dissent, we risk loosing the essence of Taijiquan in perpetuity. We have seen this (and are continuing to see this) with the practice - and the politics - associated with modern wushu. Common ground still remains for us to find when we reach out, examine the starting point and consider the inherent principles that all Taijiquan practitioners share. |

6. Evaluation and Categorization Where does all this leave us? Despite the findings of this camp or that, we are at an impasse, and the only way to move on is to avoid placing Taijiquan's origins in some simple convenient framework. Accepting any one story completely without further dialogue or research raises more questions than it answers. While there are a number of histories of the origin of Taijiquan that have merit, including the historical record of Chen Wangting, claims by lineage holders of both the Wudang Mountain practitioners and Zao Bao should not be lightly dismissed. If we are to find common ground and develop Taijiquan both as an institution and as an individual practice, it is best to pause and review the argument that the 5 major styles of Taijiquan (Chen, Yang, Wu (Yuxian), Wu (Chian Chuan), and Sun) were derived from Chen style Taijiquan as we know it today. We should continue to research (without political influence) the origins of both Chen Style, Qi Jiguang's style, and reports of pre-Chen Style Taijiquan.

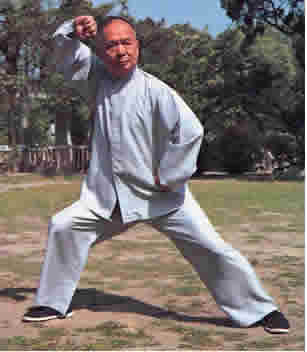

Application of Wu style "Raise Hands and Step Up" |

|

7. Is Sun Style Tai Chi Chuan a Separate Style, a Variation of Wu Yuxing (Hao) Style, or Something Else? The complications do not end here. It should be noted that the Sun Style itself is sometimes seen as a variation of Hao style, and not really as a new style. Sun Lutang based his style on on his studies of Taijiquan with Hao Weizhen (the famed master of Wu Yuxiang) style, as well as Xingyi and Bagua. Around the time when Sun Lutang developed his Nei Jia Taijiquan style, many other styles of Taijiquan were developed by Sun Lutang's predecessors and contemporaries. This was a movement and not a single development by a single teacher. Many of the internal martial art practitioners at this time, like Sun Lutang, based their developments on integrating Taijiquan with some combination of Baguazhang and Xingyiquan. A key part of this effort was to develop or revive the ancient concept of soft martial arts that became associated with the term Nei Jia Kung Fu (or Internal Kung Fu). Nei Jia Kung Fu is thought to have been originated by early Taoists who may have practiced all three arts under the umbrella of a style known as, Nei Jia Kung Fu.

|

8. Conclusion - The Continuing Development of Nai Jia kung fu This larger Nei Jia Kung Fu movement has had staying power and it has helped to develop the aspects of Yin and Yang, Wu Xing (Five Elements -- a hallmark of Xingyi practice), and Bagua (Eight Gates) in the other main styles of Taijiquan. In fact, one of the original names of Taijiquan was known as, "Ba Men, Wu Bu" (Eight Doors, Five Steps). Many of these Taijiquan styles that were developed by internal martial arts practitioners at the end of the 19th century are still around. Some of these practices have found their place within the major Taijiquan styles. In many cases, these Nei Jia Kung Fu practices are coming to the forefront as certain practitioners of these styles go public. Singling out one such development is (Jiang Rong Qiao's teacher) Zhang Zhao Dong's development of Taiji Zhang Quan which synthesized in order of emphasis (although it is very well integrated): Xingyiquan, Baguazhang, and Old Chen Style Taijiquan. (How do you count the number of people that practice this style, if this version of Taijiquan is an advanced part of the most popular combined Baguazhang and Xingyiquan system taught in China?) Another remarkable Nei Jia Kung Fu development was made by an internal stylist from the same generation as Sun Lu Tang. Wang Xiang Zai created a synthesis of Taiji, Xingyi, and Bagua principles known as: Dacheng Quan or Dacheng Kung Fu. Like most of these developments around and before Sun Lutang's time, these martial arts teachers wanted to infuse their particular concepts of traditional Bagua or Xingyi (or both) with traditional Taijiquan. In doing so, they not only made interesting developments but in some cases may have in some ways fathered new styles of Taijiquan as well.

|