This site presents information on T'ai Chi Ch'uan, Hsing-I Ch'uan, Pa-Kua Chang, and Chi Kung. The internal martial arts differ from external martial arts, in that external stylists pride themselves on training every part of their organism in relation to power and speed. Through hard work they develop kung fu. The internal martial artist trains the body in precision as well, but reaches a point where stillness in movement is achieved. In other words, pursuing the idea that less, or even nothing, can be more. That losing or yielding (not giving up) can overcome.

This is an achievement that doesn't happen overnight. It will not come to you because you practice the best style or because your teacher is prominent or famous. This comes through time, and avoiding focusing on the idea of conquering all others and, instead, focuses on a method of following or yielding (not giving up) to others. Incorrectly this is sometimes taught to mean relaxing more or moving away from others. But nothing could be further from the truth, unless you understand that relaxing is not a final achievement in the process, but rather that relaxation is a process that you engage in while you train every part of your being; every cell and fiber. Yielding but not giving up means that you are not turning your waist or sitting back to neutralize force, but using circular movements to gently introduce change in a given situation. This doesn't mean using force in a resilient matter either, to break through an opponent's guard or place force upon their stress. This, instead, means giving up to the idea of using true internal skill. Combining both the process of relaxation with strategies meant to create slight changes. For example a small rock dropped in a pond, compared to a boulder heaved in with great force.

When I first met Ma Yueh Liang, Wu Chian Chuan¹s son-in-law in 1990, he was 90 years old, but physically appeared to be in his seventies at best. Moreover, his manner was spry and young. He would practice the slow set in 30-40 minutes -- very slow, and then do the fast set with great fa-jing and power. However, at the time I was fixated with learning the Chen Style of T'ai Chi Ch'uan and the concept of silk reeling.

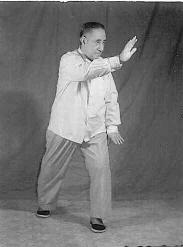

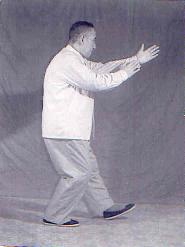

Ma Yueh Liang Performing Wu Style T'ai Chi Ch'uan (Left) Brush Knee (Right) Playing Pi Pa

Over time, I observed that Ma was able to render any movement outside of stillness to his advantage. His movements were so slight and seemingly uneventful, that to my external eye, I thought it was nothing and useless at first. With what's new and fashionable still garnering much of the attention in the uninitiated mind, it's no wonder that many flashy styles of the internal arts and modern wushu still attract a great deal of attention.

Personally, I continue to try and let go of wanting more, and instead have tried to focus on the value of less. Realizing that my ability to be effective in application relies on what others bring to the table--and how by using a process of relaxation and the quality of stillness, I am able to garner greater opportunity. To develop these attributes more, the internal martial arts practitioner might want to focus their training greatly in two areas: Standing Meditation and Push Hands.

Boxing and Wrestling are still two great ancient arts worth perusing in-depth in my opinion; especially in one's youth. However, the training in the internal martial arts focuses on the intrinsic value of stillness and the applications stillness can create and optimize.

Instead of overturning the waist or externalizing jing, small movements such as: the smallest movements that a person could possibly make while standing with their arms up curved in at shoulder level, may be the most revolutionary. Meaning that if you let go more in your elbows, you may relieve stress in your shoulders. If you can relax little by little more and more as you breathe, you will be training your fibers to engage in a process of power that seems to be coming from a seemingly unknown place, and furthermore training a calm mind to be useful in a stressful situation.

Gerald A. Sharp and Ma Yueh Liang pushing hands in a public park in Shanghai

Push Hands has often been dismissed as a training method or something for scholars, but these accolades are usually used by those who likely have no real push hands. They may believe that a high kick, a low posture, or a good series punches to the sides of the head and body of the opponent may be more useful. The latter may have value, but push hands skill can reduce the amount of stress in a self defense situation to a minimum, and keep you from being viewed as a bully when you are only trying to defend yourself.

My years of experience training both in China and in the U.S., have also shown me interestingly enough that there as many great American Teachers of the Internal Martial Arts of all cultural, racial, and ethnic backgrounds per capita as there are located in China. Not everyone in China practices martial arts, and certainly internal martial arts, and not every old person you encounter practicing T'ai Chi is a master. However, most people with little or no valid experience are looking for that old man or old woman in China who possess a certain skill or magic that can deliver them into the perfect world of the Tao. As hard as it can be to find, this dream is still there.

However, the idea that the Chinese have some superior skill simply because they are Chinese is as false as believing that Chen Style T'ai Chi is somehow superior to Yang Style T'ai Chi or any other style T'ai Chi, because it is the father of all other styles. In fact, concerning this latter point, I believe just opposite, and in this agree with the majority of Yang Style practitioners both in the U.S. and China who know that historically that the Yang Style was a revolutionary style that was introduced to the public, not as a watered down version; but a more internal form of the art.

On the other hand, some of these same practitioners of Yang Style T'ai Chi Ch'uan and their derivatives, may also believe that Pa-Kua and Hsing-I are external arts. Concerning this particular point, I don't agree. In my opinion, it depends on how you approach and follow through with the quality of your practice is what's essential. Some practitioners of the internal arts of Hsing-I and Pa-Kua believe that the application of the art lies in training in boxing skills or San Shou fighting skills. In my opinion, the Hsing-I Push Hands adept or Pa-Kua Rou Shou practitioner would provide a great deal of enlightenment to this type of practitioner.

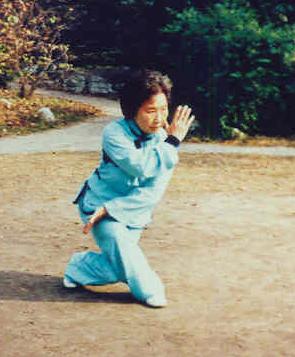

(Right - Zou Shouxian performing Pa Kua Chang)

Knowledge of the language and the culture is extremely useful to the dedicated, serious practitioner of Chinese Internal Martial Arts. The more you can learn about the language and the culture, the more ideas and concepts you will expose yourself to. This will allow you to consider on a more sophisticated level the multiple meanings that the language often suggests. For instance, song is often interpreted as "relax." But song, or fan song, also refers to the process of relaxation. A process that requires time and a personal commitment to all the attributes which create relaxation such as softness, yielding, or even exhaustion. Of these components, softness is the hardest to achieve. Even people with years of training and good yielding skills, can still be heavy and use strength to dominate or attempt to break down their opponent. However, this is not the reality of the internal arts, but instead is a false sense of strength and power.

Be wary of teachers who insist on being respected or having you salute them. It's one thing to be appreciative, but it's another to give respect to those who seek it first above being humble themselves. I can tell you that Ma Yueh Liang, who was as old school as you could get, never saluted, unless you consider putting hands together as if to pray and bowing your head a salute. His attitude was so unassuming, he never put on airs that he was the Master. If you didn't know who he was, or were unaware of his skill, you would have thought he was just a mannerly, optimistic elderly gentleman. More importantly that was how he approached the application of the art--simple, soft, and seemingly yielding.

Ma Yueh Liang performing Wu style Tai Chi Chuan White Crane Spreads Wings

Instead of thinking about how strong and powerful you are when practicing the internal arts, consider that the internal arts focus on how softness can overcome hardness. Patience, persistence, and precision can render a strength as strong as a river's current, if one considers the longer road; regardless of one's style or practice. This idea can apply to anyone whether they are a martial artist or not. Persistence can pay off. Patience, even if that means just closing our mouth and taking the time to listen to what another person has to say can be a method of beginning of going inside and training internal strength. When you are soft and still, and yet keep moving gradually together with your opponent's movement, you create the opportunity to discover your opponent's intentions and understand how best to use the least amount of force to neutralize a given situation naturally.

When this happens, you begin to appreciate others practice more, and start to learn more by watching closely. By not considering style and instead paying close attention to people's inner strength and force, you are able to ultimately see that the outer shape has little to do with what can potentially be accomplished. The internal martial artist is more concerned with listening to what's going on inside, than they are with an outer show of force.

For example, take the beginner who sees a powerful demonstration of fa-jing from the outside and sees the force erupt from the demonstrator's movements. They may even pick up on the shifting of the weight one way, while the hands go the other. However, what is missed is that the practitioner who can maintain stillness and issue force is, in my opinion, truly issuing from the internal. But again most of us enjoy a good show. But to the person initiated in the realm of the internal arts, the person who can stand still and issue, mystifies the advanced and is often unseen by the many. This issuing of force comes from being able to accomplish more with less. By using rootedness in the feet, with the ability to substantiate some joints and insubstantiate others, this issuance of energy appears to be like magic, because it happens so slightly that it¹s point of origin cannot be detected or seen.

These slight changes and differences are all around us. Stand or sit still and watch a tree and you will see the small changes and growth that take place if you are patient and still. Stillness is one of the greatest attributes of internal martial arts, and stillness and the patience to stand still for long periods of time, even when moving, is where the magic in the internal arts resides. The smaller you can be when moving or standing, the more refined your practice can become. This doesn't mean that you sacrifice the full stretch, but instead, use more of your being to accomplish it; instead of utilizing one aspect which leaves the practice one dimensional, and easily detectable ultimately by your opponent, you extend your potential by involving more of your entire being.

I remember training for competition in T'ai Chi. I was fixated with kicking higher, sitting in lower postures, and looking "perfect" I was willing to sacrifice the ability learn more about the internal with true teachers, both Chinese and American just to win. Using all my resources, I traveled greatly, and went on to win many tournaments in forms divisions. However, in my opinion, I had lost the opportunity to gain more intrinsically valuable insight and skill. And years after, I punished myself more feeling I had wasted years that I could have dedicated to self cultivation. However, because I went through that and saw so many different levels over time, as well as dealing with both winning and losing, I have been able to more fully concentrate on what is essential as time has gone by.

Concerning more on the uselessness of high kicks and low postures, I remember one time watching Ma Yueh Liang practice the slow set in his home with a group of grand students who trained in Wu Style in the People's Park in Shanghai (Grand students meaning their teachers were students of Ma.). The students made a concentrated effort, in my opinion, not to raise their leg to kick high, nor lower them self too low when pushing down. They also didn't move much, nor turn their waist grossly. The young, uninitiated student that I was, asked Ma in front of these students (as if to make my point) if it should be a goal to kick higher or squat lower. His answer was that it should be a goal to keep the Lower Dantian (located in the center, lower abdomen region of the body) at one level. When kicking stretch from there, but keep the Lower Abdomen still. Stretching to kick more from the hips. When pushing down, also stretch from there, but focus on stillness and economy of movement. Again, using the hips to lower the body downward. Zhou Zhan Fang, a senior student of Ma, also discussed this idea with me once, and pointed out pictures of both Wu Chian Chuan and Yang Cheng Fu, and how both masters were able to keep the lower dantian seemingly at one level, and stretching from it as they moved through the postures of their respective forms.

Zhou Zhan Fang and Gerald Sharp (indoor students of Ma Yueh Liang) pushing hands. Zhou Zhan Fang teaches Wu style in Shanghai (he can be reached through the Wu Chian Chuan Society) and Gerald A. Sharp teaches in Glendale California. Together, they have created a Wu style Push Hands instructional video.

This is why the idea of sitting back when moving to turn, which has become a hallmark in professional T'ai Chi Tournaments, especially both in China and now in America, is detrimental. Sitting back was designed supposedly to help beginners move easier and avoid excessive stress on the knees (thought to create T'ai Chi knee). However, nothing could be farther from the truth and just the opposite can happen. Instead, moving from the lower dantian, helps focus the energy downward, and helps movement from one Running Spring (a point known as the Yongchuan located behind the ball of the foot) even more useful and applicable. This stillness maintained in the lower abdomen can begin to release stress held in the shoulders, neck, elbows, and fingers. The movement from one running spring to the next is more fully achieved when the lower dantian is kept downward, almost pointed towards the earth, and the ankles relaxed gradually with each and every movement.

This focus on pointing the lower dantian downward, can lead to a more deeper quality of breathing. When you inhale and maintain concentration on your lower abdomen, your breathing will be gentle and easy. This not only helps to bring more oxygen into your system, but develops strength in your diaphragm to exhale at least as long as you inhale. Breathing from the diaphragm encourages chi, or fresh energy to be gathered during practice and stored in the lower dantian. Keeping the Lower Dantian or lower abdomen at one level also helps increase the ability to drop one's center of gravity without bending your knees and placing more undue pressure on the knees -- more than is necessary.

Ma Jiang Long, Ma and Wu's eldest son, and his wife with Gerald A. Sharp just after Ma Yueh Liang's death in March, 1998

So the next time you see a flashy set of moves performed, ask yourself: What is the person gaining from such practice, besides people's attention? Also ask: What more could they do with less? There's a great deal to be said for efficiency and economy.

Your comments concerning this information as presented here are welcome, and we also welcome you to check out the information about the various internal martial arts we feature on this site; as well as our store which continues to offer a wide array of instructional and demonstration material on the internal martial arts. Good Luck in your studies, and continue to persist in your practice. The pay off into a deeper exploration of yourself is rich and rewarding not only for yourself, but for those who encounter your peaceful, positive attitude, and your serenity on a daily basis.