|

1. Wudang Mountain and Nei Jia Kung Fu

In 1994, I met a notable Nei Jia practitioner and author named Pei Xi Rong. Pei's many books on Bagua, Xingyi, Taiji, and Wudang Mountain Arts are known in China and world-wide. When I met him he was still actively seeking to publish a variety of works. Pei Xi Rong was one of the five holders of the seal of Wudang Mountain's Nine Dragon Gate Sect. Knowing that I had studied Jiang's Xingyi with a senior disciple of Jiang's and with one of his own students, Pei showed me the actual seal and many of the texts on Nei Jia Arts (contemporary and ancient) both published and unpublished that he had authored. In a few of the texts, he produced pictures of the sect's practice of both external and internal forms. The internal forms practice included solo forms in Bagua, Taiji, and what he termed as an internal long fist set; as well as partner sets resembling Rou Shou and two person sword practice. Pei told me that the Nine Dragon Gate Sect was one of the few remaining groups to practice what he termed as ancient Nei Jia Kung Fu. He said that this was different than the Nei Jia Kung Fu developed in and around Beijing near the end of the 1800's by Sun Lutang and others.

He also made it a point that many more masters had been fascinated with the Nei Jia concept for centuries prior to Sun Lutang and his contemporaries. This comment has also been made by other masters that I have spoken with on the subject.

|

2. Modern Nei Jia Practice

In 1995, I witnessed, Master Pei Xi Rong teaching a group of American men what he called, "Wudang Mountain Baguazhang of the Nine Dragon Gate Sect." I was not a participant, but an observer. The Baguazhang he taught had a haunting resemblance to what is more commonly called Liang Zheng Pu, or Li Zhi Ming (Liang's student), Lao Bazhang (Old Eight Palms). This observation was verified by a student of the lineage who was a participant of the group at that time.

According to Pei, many masters including Jiang Rong Qiao and other grandmasters were fascinated with discovering the properties of their respective arts in relationship to the theories of Bagua, Xingyi, and Taiji. Pei had studied Baguazhang with Dong Wen Xou (a martial arts brother of Li Zhi Ming); Ten Animals Xingyi (or Liu He Quan) with Lu Song'gao; and 12 Animals Xingyi with Jiang Rong Qiao.

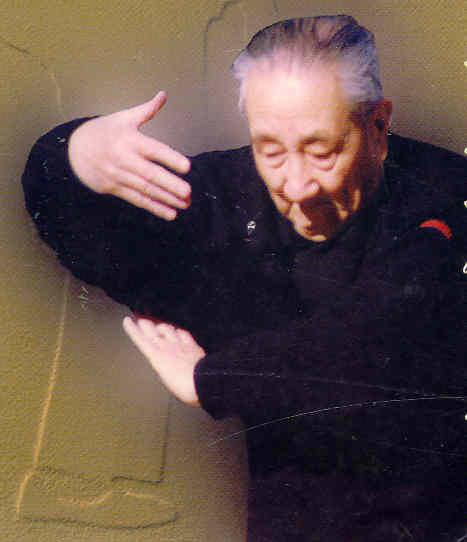

Jiang Rong Qiao walking the Bagua circle

Jiang Rong Qiao practiced and taught both Bagua and Xingyi, and developed his own Taijiquan form known as Taiji Nei Jia Zhang Quan, or Supreme Ultimate Internal Palm and Fist. This set was based on Dong Hai Quan's Baguazhang, Liu Qi Lan's Xingyi, and Chen Style Taiji's Old Frame. Jiang had studied Liu Qi Lan's Xingyi primarily from Zhang Zhao Dong (aka Zhang Zhankwei) and some from Li Cun Yi.

Jiang's fascination with Nei Jia Kung Fu led to his development of his own "Nei Jia" forms. These forms are vehicles for practicing the physical and internal concepts of the arts of Baguazhang, Xingyiquan, and Taijiquan. There are influences from the Xingyi Nei Gong and Bagua Qigong, which Jiang had studied with Zhang Zhao Dong. (This is discussed in detail in Jiang Rong Qiao's book "Xingyi Muquan" or "Xingyi Mother Fists," which has been translated by Joseph Crandall. This book is bound in plastic and available on the chiflow store website.) These sets emphasize a combination of breathing, standing meditation, energetic, yet patient movements, self-massage, and traditional Chinese health exercise practices. The Bagua Gong also features similar training with various standing postures and stepping techniques.

|

|

3. Modern Nei Jia kung fu and Taijiquan

Many of the more recently developed styles of Taijiquan have attempted to integrate aspects of Bagua and Xingyi into the style. In many styles of Taijiquan, especially those derived from Yang Style Taijiquan, the Bagua Trigrams are used to describe the hand techniques or the Quan (or Ch'uan) of Taijiquan as follows: Beng (Ward-Off & Assessment), Lu (Diverting), Ji (Pressing), An (Pushing Down), Cai (Plucking), Li (Twisting), Zhou (Elbowing), and Kau (Leaning). While Jin (Stepping Forward), Tui (Stepping Backward), Ku (Looking Left), Pan (Looking Right), and Zhong Ding (Central Equilibrium) are related to Wu Xing (Five Elements) the guiding principles behind traditional Xingyi practice.

Wu style Taijiquan provides an excellent example of an attempt at this integration. Wu Style Taijiquan incorporates the philosophies underlying both Xingyi and Bagua within the art. The founder of this style was Wu Chian Chuan. His classic treatise penned in his own hand was known as "Ba Men, Wu Bu" (which translates into English as "8 Gates, 5 Steps"). This book discusses many aspects of Wu Xing (5 Elements) and Xingyi, as well as Bagua and the 8 Trigrams that are prevalent within the internal art of Taijiquan.

Wu style application from Lan Cai Hua form

Wu Chian Chuan's son-in-law and perhaps his student that achieved the most advanced level of practice was Ma Yueh Liang. In 1990, I became an indoor student of Master Ma Yueh Liang and his wife Master Wu Ying Hua in Shanghai. I had the privilege of learning Wu Style's Xingyi form as well as the Lan Cai Hua form. (The Lan Cai Hua is mentioned in Ma Yueh Liang's book as an important form in Wu style Taijiquan.) The Lan Cai Hua form incorporates footwork that is somewhat similar to Bagua's. The Lan Cai Hua foot movement follows the "S Curve" and not the circumference of the yin - yang circle. Wu's Hsing I on the surface appears to be similar to Traditional Hebei Style Hsing I. However, it combines aspects of Wu's Traditional Form with a horse stance on a precise angle to deliver either a nasty rib shot or an oblique push with a fist.

In teaching me Wu Style Taijiquan, Ma Yueh Liang once penned in his own hand the Ba Men (or Eight Doors) as the symbol for the Post Heaven Trigrams of Baguazhang, or Cyclical representation. Notably Ma Yueh Liang's presentation was different from many books on the subject by prominent masters who historically drew the Eight Doors as only the Pre-Heaven Bagua symbol emphasizing a polar distinction. This historical presentation was most likely done to emphasize Taiji's foundation in Yin and Yang. Ma discussed the polar view or Pre Heaven symbols as a method of reading the opponent's intentions or central equilibrium. This aspect of Wu style Taijiquan theory he called "the Eight Doors" and it is presented in his book on Taiji Tuishou (Push Hands). Ma Yueh Liang reserved the Post Heaven or cyclical symbol as a systematic presentation of hand techniques.

Ma projected the Eight Doors on his opponent, with the center as the opponent's heart. If he sensed hardness in the opponent's left shoulder, for example, he would attack or follow the opponent's right hip. This is a gross, or large circle, application, which over time is reduced to the size of a bull's eye.

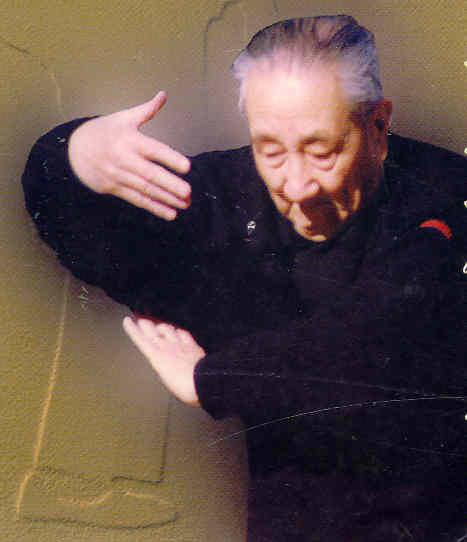

Ma Yueh Liang performing a Wu style Chi Kung exercise

Ma Yueh Liang applied this Eight Doors theory in his practice. Using Ting Jing (audible force), Ma could locate an opponent's center from their breast bone straight through to their back. With these skills, Ma was able to expose the center of balance of an opponent as well as the intention of their movements. This evaluation or "listening" can take place quickly. Because the opponent's center was exposed in this way, and their intentions are known, the response could be subtle and employ a minimum of hard force. In Ma's house on Fu Xing Zhong Lu in Shanghai, I saw a young American martial arts instructor go flying across the room to land upside down on the sofa when he tried to "go in hard and fast" on Ma Yueh Liang (then in his ninties). This is one of many examples in which Ma was able to employ softness to overcome an opponent's hardness.

|

4. A Personal Perspective

It is possible to view Nei Jia Kung Fu either as something discovered by one person at the turn of the last century or as a centuries old search to discover the power of the internal aspects of human potential. In either case, this potential for growth and insight can manifest itself in interesting ways. There are vast possibilities in cultivating determination, patience and acceptance in the process of self-discovery. The practice of Nei Jia Kung Fu relies on the joints, softness and flexibility rather than on muscle, speed and might. A person skilled in Nei Jia kung fu can continue to improve their skills into old age. The Approach of Nei Jia kung fu can be applied to the study of a wide range of endeavors in many parts of your life.

This viewpoint drives a slightly different approach to the practice of Nei Jia kung fu. Novices sometimes ask which instructor they should practice with locally, or who is the present lineage holder in a certain style or who is the best reactionary. The truth is that it can be very difficult to evaluate teachers without enough of a background to provide appropriate context. Most people evolve through several different sets of ideas about the nature of the practice of internal kung fu and their interests and priorities. To make things even more difficult, many of the teachers are often not teaching Nei Jia kung fu in a way that is likely to take their students very far.

For example, there are several approaches to teaching Wu style Tai Chi Chuan. The instruction approach that is most commonly used teaches only the Wu style long form. This approach can work if you can focus on the main principles (they are laid out in several places including Ma Yueh Liang's orange book) and if you persist in regular practice. Having said this, Ma Yueh Liang usually followed a different approach to teaching students. Ma taught the Wu long form to the first cross hands and then usually introduced the student to push hands practice. After this, the form instruction continued in parallel with instruction related to push hands (such as the solo two hands exercise described in Ma Yueh Liang's Push Hands book). Ma instructed the individual students depending on their own level, but there was a wealth of supplemental instruction. Every teaching day, the core practice began with the student demonstrating a form (usually either the long form or the simplified form). A traditional form was always performed before anything else, no matter what the topic. Ma would then provide specific feedback on the form demonstrated. Then the supplemental or ongoing instruction that Ma Yueh Liang presented took place. That day's instruction, even if one was studying spear for example, would often emphasize any issues uncovered in the initial form's demonstration. This approach would help strengthen any weaknesses uncovered that much more. In this way, Ma was an effective teacher. Using what you were doing to evaluate, instruct, and build on. That is why many of his inner door students, regardless of whether they were from inside China, Europe, U.S., or anywhere, were able to advance and assimilate in-depth knowledge.

The practice of Hsing I Chuan is often presented as exclusively a striking art that projects hard force outside the body. Teaching Hsing I Chuan in this way turns it into a system that is so external that it seems to be little different from karate. I have studied three styles of Hsing I Chuan, and all three teachers emphasized aspects of Hsing I based on their own skills and ideas (demonstrating Hsing I Ch'uan's flexibility). All of my teachers were very aware of Hsing-I's internal applications. Whether or not they were very skilled at the internal practice themselves, these teachers presented Hsing I Ch'uan's softer side as the ultimate focus. It was the way the art of Hsing I Ch'uan was traditionally taught, whether the student started with this emphasis or not.

The practice of Pa Kua Chang can be taught as a branch of modern Wushu, or a martial art style with its foundation in speed that is performed as techniques that are separated from the actions of the opponent. Teaching Pa Kua Chang with this approach turns it into an external martial art. There is no place in this sort of system for Rou Shou. Rou Shou is a Pa Kua variant of push hands practice that includes striking. I feel that the practice of Rou Shou is a central part of the development of Pa Kua as an internal art. This is because all styles of Nei Jia kung fu are designed to exploit the instances when an opponent separates. The proper speed and the correct application of a Pa Kua technique both depend on the evolving dynamical situation, which is partly determined by the opponent.

|

|

5. Conclusion

It is disturbing to me how the internal aspects of Taijiquan, Xingyiquan, and Baguazhang are often ignored, and even at times rejected, as they are now taught. The internal approach I have discussed is simply not the way that many schools teach. There are some compelling reasons for this situation. Nei Jia kung fu practice often does not "look" martial; perhaps it does not look martial enough to be commercial or to support a viable school. Perhaps it takes too long to achieve proficiency. The study of Nei Jia kung fu requires commitment, and it is not well suited for those who are looking to escape reality. The path of Nei Jia kung fu requires discipline, commitment, patience, an ability to see things as they really are without loosing optimism, and a willingness to accept adversity while seeking opportunities. The results of this approach can yield rewards that seem almost miraculous. Furthermore, the approach of Nei Jia Kung Fu can be applied to many parts of life.

There are other problems in transmitting internal kung fu. These problems range widely. There are instructors taught by teachers with good skills and good intentions that are not training high-level students. It remains easy to inflate a teacher's lineage claims and hard to know if even a valid lineage claim says anything about the teacher's actual skill level. Quite a few teachers have some knowledge, but not enough skill to train high-level students. Some teachers attempt to make internal styles more commercial by adding external practices. Finally, there are teachers that I can only view as frauds. I have been deceived by more than my share of frauds and disingenuous teachers. (This is still a huge pit-fall for new students.) I have also had the good fortune to study with some particularly great teachers.

A key part of the failure to pass on the art of Nei Jia kung fu probably involves "secret knowledge." Some teachers tout what they refer to as secrets in an attempt to shroud the art in mysticism or as a scheme to control their students. The truth is that the teachers I've met with any real skill have never referred to their art as having secrets. My teachers did take the traditional view that inner door forms should taught only to students considered "close" or "disciples," but there were a range of attitudes about what should be kept private. On one end of the spectrum, some teachers - including Ma Yueh Liang - played down the whole notion of secrets so much that he taught the inner door forms and applications to anyone who was committed to long term study with him (disciple or otherwise). On the other end of the spectrum, I know of teachers from families renown for their skill that have few - if any - high level students;

their schools seem unwilling to teach the majority of the art because they regard it as secret.

Again, it is my hope to make chiflow.com a source for more information about Nei Jia Kung Fu. It is my intention that chiflow will make available materials on the many aspects of Nei Jia Kung Fu. I hope that information on chiflow.com keeps people from repeating some of the mistakes that I have made and allows them to share in the some of the benefits that I have gained.

|

Pictures

Martial Arts Tournament

.jpg)

Emei Mountain Training

Chen Fake Pushing Hands |

Examples of early Nei (Internal) Jia practice can be found in the developments that were made in Qigong. For example Qigong's guiding principle is harmony, classical Chinese philosophy such as Yin and Yang as its theoretical base, the use of will power as its fundamental means, a combination of motion and stillness as its form of expression, and mental, physical, and spiritual work as its goal. Qigong's roots are found in Daoyin which practiced quieting and focusing the mind in order to gather energy. This is as opposed to modern forms of exercise, which require both the display of one's strength and skill and consumption of energy.

Examples of early Nei (Internal) Jia practice can be found in the developments that were made in Qigong. For example Qigong's guiding principle is harmony, classical Chinese philosophy such as Yin and Yang as its theoretical base, the use of will power as its fundamental means, a combination of motion and stillness as its form of expression, and mental, physical, and spiritual work as its goal. Qigong's roots are found in Daoyin which practiced quieting and focusing the mind in order to gather energy. This is as opposed to modern forms of exercise, which require both the display of one's strength and skill and consumption of energy.

Our store site has many Taijiquan books and videos that you can find only here.

Our store site has many Taijiquan books and videos that you can find only here.

.jpg)